Analysts and pundits talk about “bull” and “bear” markets all the time. Lately there has been a lot of talk about a bear market in stocks, and whether we have entered one. If you are wondering what a bear market in financial markets means exactly, you are not alone: as well as being a broadly subjective definition of a market where prices can be expected to trend downwards, i.e. fall in value, there are a few different technical definitions used to define trends.

Classic Definition of a Bear Market

The classic technical definition of a bear market is a 20% fall in value from their respective peaks by multiple major stock indices, over a period lasting at least two months. From this it can be seen that there can be a bear market in one sector, country, region, or even over the entire world.

Few “Classic” Bear Markets Yet

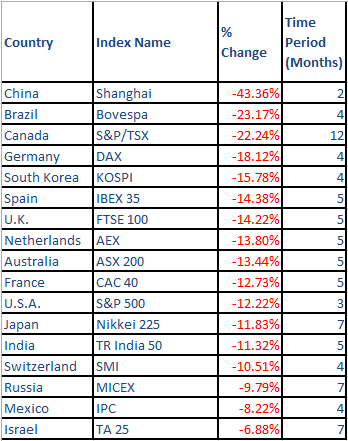

Taking this classic definition as a starting point, let’s examine whether there are any countries whose stock markets meet the criteria. The table below shows the major stock market indices of various countries, and how much each index has declined from its recent market top.

According to the classic definition, it can be seen that of the roughly representative sample of widely quoted global stock market indices, only three can be said to indicate bear markets in progress: China, Brazil and Canada. Germany is close and as the major economic power within the European Union, that is significant. It is worth noting that the Dow Jones Industrial Average, typically regarded as a stock market index in the U.S.A. that is almost as key as the S&P 500 Index, is down from its peak by only 16.09%, so that does not indicate a bear market in the U.S.A. either.

We cannot really say there is a global bear market in stocks yet, although it can be seen easily that every stock market is down from its recent peak, and down quite significantly. The trends everywhere are undoubtedly down. Is this not indicative that markets look bearish everywhere?

Bear Market vs. Correction

This disconnect is probably best explained by the fact that a multi-month trend can still be considered a “correction”, even if its peak is a significant market top. Following the classic technical definition, most countries are in a bearish correction to their longer-term bull markets. For example, the S&P 500 might look very bearish right now, but if you take a long-term view and pull out a multi-year chart, the recent fall in prices looks possibly minor and temporary. Take a look at the monthly chart of the last 10 years:

The final candlestick shows the current month and it is indeed a sharp fall. However, if you look at it in context, it is just a pretty large blip in an amazing upwards move that began in 2009 and produced a 200% increase in the value of the index.

Other Methods to Determine a Bear Market

It might be that the classic method of waiting for a 20% drop in a financial market to call a bear market leaves the matter a little too late to be of much use! Historical studies show that downwards moves in stock markets usually happen much more quickly that upwards moves, as the value of stocks tends to rise over time. Therefore if you want to sell stocks that you own, either for profit or to protect against loss, it is probably wise not to wait until a market has fallen by 20% in value from its most recent peak. That might be too much profit to sacrifice. Fortunately there are a couple of other widely tested methods for determining when a bear market has begun, which I touched on in my recent article about how to trade stocks using the Livermore method.

The first method is to wait for 2 consecutive monthly closes both either above or below the 12 month simple moving average, derived from monthly closing prices. Moving averages can identify market turns more quickly as they create a relative scale, while just relying on an arbitrary number such as a 20% decline from a peak might well produce more arbitrary results.

Looking at the chart above, using this method would have sent you bearish in March 2008, before getting you bullish again in April 2009. It would have got you into that bear market 200 full points before the 20% drop happened. It then would have kept you bullish from April 2009 until October 2011, when it again signaled a bear market. Waiting for a 20% drop from the peak would have produced the same result, so that would have been no better. Then the moving average method would have got you bullish again in March 2012, and you would still be in. So over the last 10 years, the 12 month moving average method has performed better on this index in calling the state of the market than the classic 20% rule.

Finally, there is another well-known method using the crossings of two moving averages, instead of the previous method described where the price itself must close above or below a moving average. This plots a 50 day moving average against a 200 day moving average. A bull market is said to begin when the 50 day moving average crosses above the 200 day moving average. This is widely known as a “golden cross” or “bull cross”. Conversely, a bear market is said to begin when the 50 day moving average crosses below the 200 day moving average. This is widely known as a “death cross” or “bear cross”.

If we look at this method applied to a similar time frame on the same index, we can see that it produces fairly similar results to the 12 month moving average method outlined earlier. Note that we are right on the verge of a “bear cross”.

Conclusion

The classic technical definition of a bear market is too slow to be used as an effective top-down market timing method for trading stocks as a bull or bear. Either of the two moving average methods outlined previously tend to produce better results.